The Anthropophagist Manifesto (Intro)

Oswald de Andrade published the Manifesto Antropófago in 1928. In 1991, Leslie Bary created an excellent and widely cited translation. In coming (non-consecutive) posts, I offer my own translation, not in competition with or as a replacement of hers, but rather to show the possibilities of a text that was important in 1928, and only became more so over the years. As Bary notes in her introduction, the Manifesto Antropófago “has, especially in the last twenty years, been widely cited in Brazil as a paradigm for the creation of a modern and cosmopolitan, but still authentically national culture.”

The manifesto originally ran on two (non-consecutive) pages in the Revista de Antropofagia (“Anthropophagy Review” and/or “Anthropophagy Magazine”), taking up the entirety of page 3 and two-thirds of page 7, as a series of 52 (mostly) short, aphoristic snippets. This approach is part of what complicates this text, which is full of, in Bary’s words, “joking and punning references to Brazilian history and to sometimes obscure informing works.” (Bary’s translation provides a large number of very helpful annotations to these references.)

TITLE: The Bary translation is entitled the “Cannibalist Manifesto.” I have chosen “Anthropophagist Manifesto” in large part because “cannibalism” comes burdened with many stereotypes in American culture. “Anthropophagy” also has the advantage of referring specifically to eating humans (whereas cannibalism can be any species eating itself). I acknowledge that this is a difficult, unusual word that causes one to hesitate when reading. However, that is part of the reason I like it because it forces the reader to pay direct (meta) attention to the cultural project itself rather than getting lost in the text.

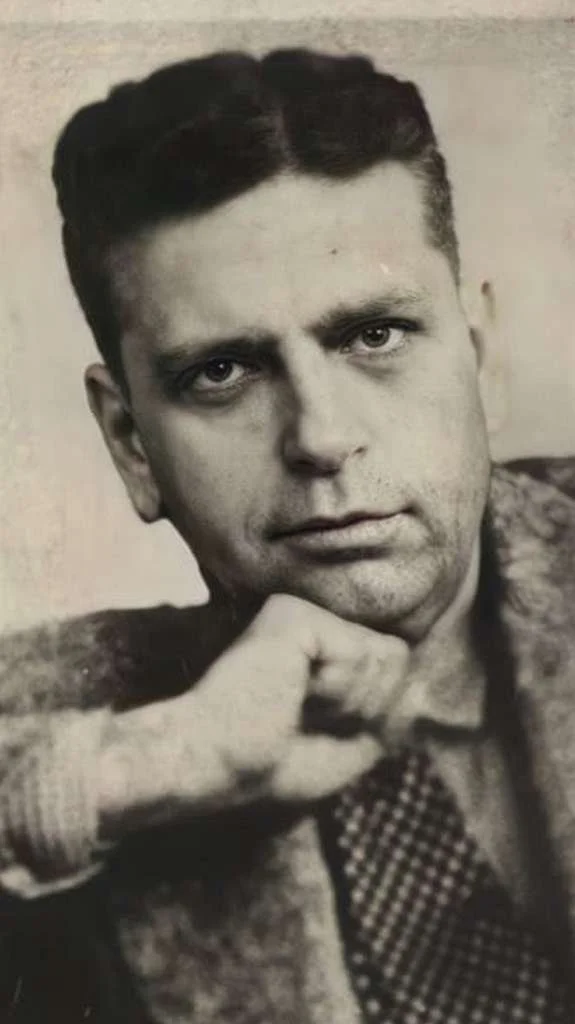

CLOSING: Oswald signed the manifesto

OSWALD DE ANDRADE.

In Piratininga.

Year 374 since the Deglutination of Bishop Sardinha.

São Paulo dos Campos de Piratininga was founded in 1554 with the inaugural mass of a Jesuit school. It eventually grew into the city we now know as São Paulo, where Oswald wrote his manifesto.

Pedro Fernandes Sardinha studied theology at the University of Paris and taught at the universities of Coimbra and Salamanca. He arrived in Brazil as the bishop-designate on February 25, 1551, and was ordained and took on the role on June 22, 1552. He was summoned back to Lisbon in 1556, embarking on the ship Nossa Senhora da Ajuda (Our Lady of Good Help), which on July 16, 1556, wrecked near the mouth of the Coruripe River. The passengers were captured by Caeté, who apparently killed and ate them.

In the purple prose of Simão de Vasconcellos’ marvelously titled, but inevitably apologist 1663 “Chronica da Companhia de Jesu do estado do Brasil e do que obraram seus filhos n'esta parte do novo mundo em que se trata da entrada da Companhia de Jesu nas partes do Brasil, dos fundamentos que n'ellas lançaram e continuaram seus religiosos, e algumas noticias antecedentes, curiosas e necessarias das cousas d'aquelle estado” (in Old Portuguese, “Chronicle of the Society of Jesus in the state of Brazil and of what its sons built in this part of the new world in which is described the entrance of the Society of Jesus into the parts of Brazil, the bases on which they launched themselves therein and continued their religious acts, and some preceding, curious, and necessary news about things in that state”):

Em uma enseada, junto a este rio, alguns anos depois, sucedeu o triste desastre do naufrágio do bispo D. Pedro Fernandes Sardinha, primeiro do Brasil, que dando nela á costa, foi cativo dos índios Caetens, cruéis e desumanos, que conforme o rito da sua gentilidade, sacrificaram à gula, e fizeram pasto de seus ventres, não só aquele santo varão, mas também a centena e tantas pessoas, gente de conta, a mais dela nobre, que lhe faziam companhia voltando ao reino de Portugal.

In a cove near that river, some years later, occurred the sad disaster that was the wreck of the ship containing bishop D. Pedro Fernandes Sardinha, the first of Brazil, which crashing into that coast was captured by the cruel and inhuman Caeté, who according to the rites of their gentility, sacrificed them to gluttony, grazing on their entrails, not just those of the holy man, but also one hundred and some persons, people of rank, the majority of them noble, who were accompanying him on his return to the kingdom of Portugal.